In July 1957 Warren Harding, Mark Powell and Bill Feuerer began what became one of the most controversial first ascents of the time. Unlike the single-push ‘alpine’ style used on the recent Half Dome climb by Royal Robbins and his group, they chose to fix lines between ‘camps’ similar to that used in the Himalaya style mountaineering. The team would fix ropes at varying points along the route, climb during the day and rappel down at night to have dinner and sleep in Camp 4. Many climbers at the time thought this type of climbing wasn’t in the true spirit of big wall climbing and that Harding’s attempt shouldn’t count as a “first ascent”.

Harding and his group began their ambitious endeavor. During the first push Harding and his group managed to get half way but soon encountered huge cracks in the granite. Feuerer set about to cast new pitons big enough for the monstrous cracks. Unable to find anything suitable to make a piton big enough to wedge into the huge cracks Feuerer finally came across the legs of a cast-iron wood stove. Estimating that the legs would be just about right he cut them off and drilled a hole for the rope the rope. The crack system would later be named after Feurer’s monstrous stove leg pitons and are today known as the ‘stove leg cracks”.

During Hardings “siege” (as many climbers thought of it) of El Cap word spread like wildfire and people from all over came to see the men attempting to conquer what many thought could never be climbed. The crowds in El Capitan Meadow became so huge that the National Park Service asked Harding and his group to stop until after Labor Day. Warren was forced to put the ascent on hold.

At a time when many unclimbed routes were being ascended for the first time there was a big push in the climbing community to be “the first” to climb something. Climbing groups in Camp 4 would form at the drop of a hat and teams would set off to conquer some yet unclimbed portion of the park. During one of these trips Powell suffered a compound leg fracture and was forced to drop out. Seeing that the team was falling apart and there were many other first ascents taking place and the El Cap endeavor was taking too long, Feuerer dropped out also leaving only Harding.

Harding began searching the camp for new partners looking for ‘whatever “qualified” climbers I could con into this rather unpromising venture.’ Feuerer stayed on to help as technical advisor when he wasn’t doing other climbs and even constructing a bicycle wheeled ‘cart’ to haul the heavy ropes and gear back and forth to Camp 4 every night. Wayne Merry, George Whitmore, and Rich Calderwood now became the main team, with Merry sharing lead chores with Harding.

In the Fall, two more pushes got the team to the 2,000 foot level. Finally, a fourth push starting in the late Fall would likely be the last. In the chilly November air, the team worked their way slowly upward pushing within 300 feet of the top.

After sitting out a storm for three days just 300 feet from the top the team decided it was time to finish the climb and began hammering their way up the final portion. Harding struggled fifteen hours laboriously drilling and placing 28 expansion bolts by hand through the night up an overhanging headwall, topping out at 6 AM. After 45 days (or 47 depending on who you ask), of more than 3400 feet of climbing it was done. El Capitan had been conquered.

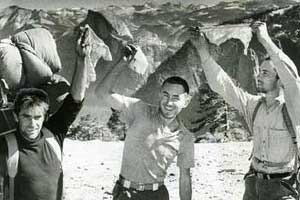

Warren Harding, Wayne Merry and George Whitmore, (l to r), wave their handkerchiefs after scaling what had been until then unclimbed face of El Capitan.

In 2008, the 50th anniversary of the climb, the team was officially recognized by the US House of Representatives who passed a resolution honoring their achievement.

So what are you going to do today?